The myth and reality of "physics-based" models in geosciences

Welcome to GeoAI Unpacked! I am Ali Ahmadalipour and in this blog, I share insights and deep dives in geospatial AI, focusing on business opportunities and industry challenges. Each issue highlights key advances, real-world applications, and my personal takeaways on emerging technologies.

In this article, I’ll unpack why many so-called physics-based models in Earth sciences aren’t as purely physical as we think, and what that means for how we model the world. ❗️A reminder that these are my personal observations and opinions, and do not reflect the views of my employer. Let’s dive in!

Here’s a 5 min summary of this article for those who prefer watching a video:

1. Introduction

Across hydrology, fire, weather, and climate science, models are often described as physics-based—a phrase that evokes rigor, transparency, and trust. Yet, beneath the surface, much of what drives these models are empirical relationships and parameterizations rather than direct solutions of physical laws. These assumptions are necessary to make the equations computable, but they also introduce biases, tuning artifacts, and uncertainties that can propagate through every layer of simulation.

This doesn’t mean physics-based models are flawed or obsolete; rather, it highlights the complexity of modeling natural systems. In recent years, data-driven and hybrid approaches have emerged not to replace physics, but to complement it—sometimes reducing error, sometimes improving scale transfer, and often challenging long-standing assumptions about what “physical realism” truly means.

2. What “physics-based” really means

In theory, a physics-based model is one that derives its predictions directly from the governing equations of the natural system. For instance, the Navier–Stokes equations for fluid flow, the Richards equation for soil moisture, or energy balance equations for land–atmosphere exchange. These formulations embody physical principles like conservation of mass, momentum, and energy, giving the models a sense of scientific authority.

In practice, however, most geoscience systems are far too complex and multiscale to be represented in their full physical form. Processes like infiltration, evapotranspiration, convection, or fire spread occur at spatial and temporal scales far smaller than model grids can resolve. To compensate, scientists introduce parameterizations; empirical relationships that approximate the collective behavior of unresolved processes. Over time, these parameterizations have become a defining feature of physics-based modeling itself.

The result is a hybrid architecture: equations grounded in physics but heavily shaped by empirical tuning. This approach is not inherently bad (it actually makes models run efficiently) but it does blur the line between physics and empiricism. Many of the “constants” we treat as physical are, in reality, calibrated coefficients that vary across regions, datasets, and even software versions.

Here’s an example:

Take hydrologic modeling: many rainfall–runoff models claim to be physics-based because they include components such as infiltration, evapotranspiration, and surface flow derived from physical laws. But a closer look reveals that key components like how soil transmits water are often governed by empirical equations such as the SCS Curve Number methods. These formulas were originally derived from limited field experiments and then generalized through calibration rather than universal physical constants.

Similarly, large-scale land surface models in climate systems include processes like canopy interception or root-zone moisture uptake that are tuned to reproduce observed fluxes, not measured directly from first principles. Even though the overarching structure looks physical, the predictive power often depends on how well these tuned parameters represent the local reality. When applied beyond their calibration range (e.g. in a different climate regime or soil type) the errors can grow quickly.

3. Where uncertainty creeps in

Every model, no matter how sophisticated, carries uncertainty. In geosciences, much of that uncertainty stems not from randomness in nature, but from the structural and empirical choices within the models themselves. When parameters are tuned rather than measured, and when simplifications replace physical detail, each assumption adds a new layer of uncertainty to the system.

These uncertainties compound across multiple sources:

Input data and forcing errors: for example, rainfall estimates that drive flood or hydrology models are often biased or sparse.

Parameter calibration: different combinations of parameters can yield similar outputs (known as equifinality), masking model weaknesses.

Structural simplifications: models designed for one catchment, soil type, or vegetation class often fail elsewhere.

Scale mismatches: fine-scale processes like infiltration or convection are averaged over coarse grid cells, distorting the underlying physics.

The cumulative effect is that two “physics-based” models, each grounded in conservation laws, can produce vastly different outcomes under identical conditions. Hydrologists see this in the wide spread of flood predictions across basins; climate scientists see it in diverging projections of future rainfall or temperature extremes among general circulation models (GCMs).

What makes this particularly challenging is that model uncertainty is often systematic rather than random, and biases are baked into the structure and calibration of the model itself. This means that even with perfect input data, the model can still yield consistently wrong results for the wrong reasons.

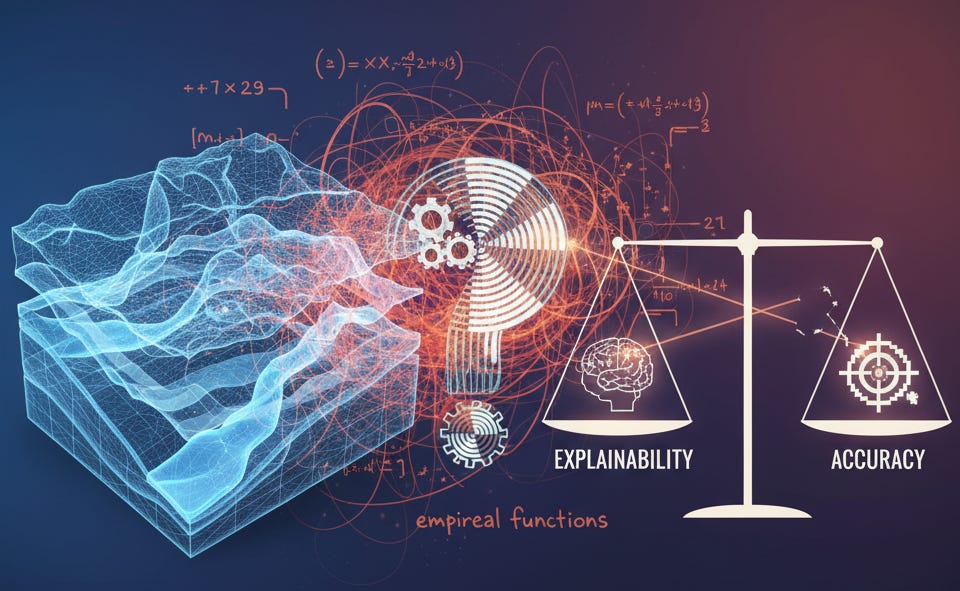

4. The error–explainability dilemma

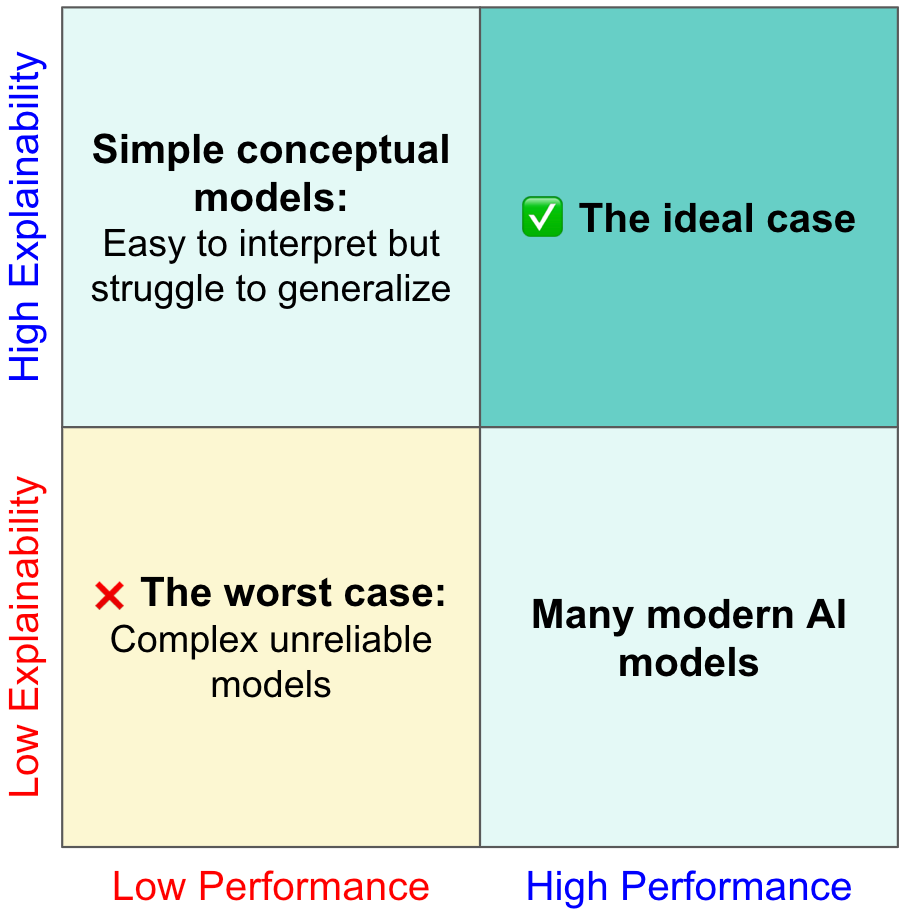

When we talk about model performance, it’s tempting to focus only on accuracy. But accuracy alone doesn’t tell the whole story. In geoscience models, we often face a trade-off between how well a model performs and how clearly we can understand why it performs that way.

The following figure shows this dilemma, with model performance on one axis and explainability on the other. The ideal scenario is, of course, a model that combines low error with high interpretability, but that’s rarely achieved in practice. Most models fall somewhere in between, balancing accuracy, complexity, and transparency in different ways. In reality, many “physics-based” models end up explainable in theory but riddled with empirical components that obscure cause-and-effect, making it difficult to trace errors or generalize beyond calibration ranges.

5. Beyond accuracy: Practical considerations

Model performance is only one piece of the puzzle; practical considerations often determine whether a model can actually serve its intended purpose. Once deployed, factors such as maintenance, computational cost, and adaptability become just as important as accuracy or physical rigor.

Ease of maintenance: Both physics-based and data-driven models require updates over time as new data, boundary conditions, or system behaviors emerge. However, the nature of these updates differs. Physics-based models often involve manual recalibration and parameter adjustment, which can be labor-intensive and reliant on expert judgment. Data-driven models, on the other hand, can be retrained automatically but still need careful monitoring to prevent model drift and ensure consistency with physical constraints.

Cost to train or calibrate: Traditional calibration of physics-based models demands expert time, domain insight, and iterative tuning. AI training requires significant up-front compute but is largely automated once the data and architecture are in place.

Cost to operate: Running large-scale physical simulations can be computationally intensive, especially for high-resolution flood or climate models that demand supercomputing resources. After training, AI models typically offer much cheaper inference, producing rapid results on standard hardware.

Scalability and adaptability: Physics-based models are often built for specific domains or regions and can struggle when transferred to new geographies. Data-driven models, if designed carefully, can adapt more easily to new inputs or scales.

In the end, the best model is not always the most accurate or the most “physical”. It is the one that delivers reliable insights, operates sustainably, and can evolve with changing data and understanding.

6. Data-driven and hybrid pathways

The growing interest in data-driven methods is not about replacing physics; it’s about expanding the modeling toolkit. In many geoscience applications, AI can act as a complementary layer that reduces computational cost, improves spatial and temporal resolution, or captures nonlinear relationships that traditional parameterizations often miss.

In flood or rainfall–runoff modeling, machine learning models such as LSTMs and graph neural networks have shown that it is possible to predict river discharge or soil moisture directly from meteorological inputs without explicit calibration of physical parameters. In weather forecasting, models like GraphCast and FourCastNet have outperformed numerical weather prediction models. I wrote an article on this topic last year that goes into more details about weather forecasting:

A promising direction lies in hybrid approaches that integrate the strengths of both worlds. Physics-informed neural networks (PINNs), neural emulators of numerical solvers, and AI-driven data assimilation frameworks are examples of models that embed physical constraints into learning. These systems retain the interpretability and stability of physics-based approaches while benefiting from the flexibility and speed of machine learning.

The practical advantage of such integration is adaptability. As data availability grows and physical understanding improves, hybrid models can be continuously refined without fully discarding existing frameworks. Instead of viewing AI as a challenger to traditional modeling, it can be seen as an accelerant that modernizes and strengthens it.

7. Towards fit-for-purpose modeling

Rather than debating whether physics-based or data-driven models are superior, the more meaningful question is fit for what purpose? Each modeling approach brings its own assumptions, constraints, and strengths, and the right choice depends on the problem being solved, the data available, and the level of uncertainty one can tolerate.

Physics-based models remain indispensable when we need to explore counterfactuals or simulate future scenarios under changing conditions. Their strength lies in explicit causality and the ability to represent processes beyond the range of historical data. Data-driven models, by contrast, excel when large volumes of observations are available and the goal is accurate, fast, and localized prediction. They can learn complex nonlinear relationships directly from data and are often easier to scale and update once a robust pipeline is in place.

The most promising direction, however, lies in integration rather than replacement. Hybrid models that use physical insight to guide AI, and AI to fill observational or structural gaps, can provide both stability and adaptability. The future of geoscience modeling will likely depend on how effectively we combine these paradigms, not on which one “wins.”

Ultimately, the objective is not to defend a modeling philosophy but to design tools that help us understand and anticipate Earth’s behavior under uncertainty.

8. Conclusion: A call for modeling realism

The idea of a purely physics-based model is as elegant as it is elusive. In practice, most geoscience models are built on a mosaic of physical laws, empirical relationships, and calibrated parameters, each contributing to both their usefulness and their uncertainty. Recognizing this doesn’t undermine their value; it simply grounds our expectations in reality.

Data-driven methods are not a replacement for physical understanding, but a way to enhance it. By capturing patterns that equations can’t easily express and by offering faster, more adaptive tools, they open new pathways for exploration and prediction. When combined thoughtfully with physical reasoning, they can reduce complexity rather than add to it.

As modeling continues to evolve, the goal should not be fidelity to a tradition (whether “physics-based” or “AI-based”) but fidelity to the problem itself. The future of geoscience modeling lies in this pragmatic balance: using physics where it matters, data where it helps, and transparency everywhere.